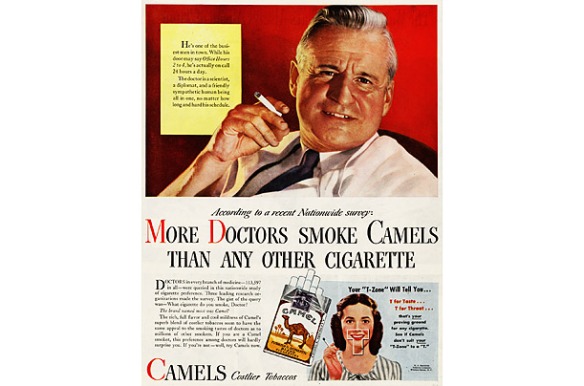

Back in the good old days of marketing, health care professionals were among the most trusted and convincing shills for cigarette companies. Let’s revisit some classic ads for smokes that came highly recommended from those is high places . . .

.

A medical specialist reports: “No adverse effects on the nose, throat and sinuses from smoking Chesterfield!”

.

This series of Camel ads began in 1947 and ran for six years. One ad reassured smokers that this headline was an “actual fact,” not a “casual claim.”

.

American Tobacco was among the first companies to mention physicians in cigarette advertising ads. Their “toasted” claims did not reflect the reality that their curing process was identical to all other cigarette manufacturers.

.

And they make your teeth nice and yellow, too . . .

.

One of the last cigarette ads claiming a doctor’s endorsement, this 1954 ad in Life magazine showed Hollywood star Fredric March making this assertion after having read the letter written by a “Dr. Darkis” that was inset into the advertisement. Dr. Darkis explained in this letter that L&M filters used a “highly purified alpha cellulose” that was “entirely harmless” and “effectively filtered the smoke.” Darkis was not a physician, but a research chemist.

.

Coincidentally, cigarette ads also began appearing in the pages of medical journals for the first time in the 1930s as tobacco companies worked to develop close, mutually beneficial relationships with physicians and their professional organizations. These advertisements became a ready source of income for the next 20 years for many medical organizations and journals, including the New England Journal of Medicine and the Journal of the American Medical Association.*

And as recently as 1969, Post-Keyes-Gardner, the ad agency for tobacco giant Brown & Williamson, relied on the paid testimony of physicians for a new campaign “to set aside in the minds of millions the false accusations that cigarette smoking causes lung cancer or other diseases.” **

* Cummings K. M., C. P. Morley, and A. Hyland, “Failed Promises of the Cigarette Industry and Its Effect on Consumer Misperceptions About the Health Risks of Smoking,” Tobacco Control 11 (Suppl 1) (2002): I110–I117, and R. W. Pollay, “Propaganda, Puffing and the Public Interest: Cigarette Publicity Tactics, Strategies and Effects,” Public Relations Review16 (1990): 27–42.

** (Handbook of Public Relations, Heath & Vasquez, 2004).

.

See also:

- Vintage ads we’ll never see again

- More vintage ads we’re not likely to ever see again

- And more vintage ads we’ll never see again

- And even more vintage ads we’ll never see again

.

And I wonder what we will think of doctors endorsing statins and SSRI’s in 20 years time?

I wonder the same thing, Dr. Joe!

Especially the ones who tell patients that statins should be in the water supply.

Thanks! This nicely illustrates two concepts often used as justification for various treatments:

(1) Expert opinion

(2) Mechanism of action

Note that expert doctors are used to endorse smoking. And there is mention of the theoretical reasons why smoking should be fine (filters, alpha-cellulose). A more rational approach is to simply look at OUTCOMES.

Good points, Mark. Alas, so much of health care is focused on treating to numbers, not on actual outcomes.

I just scrolled through every one of your linked collections of vintage ads. The unselfconscious misogyny. Heroin for coughs.

And remembered discussions with much younger coworkers who opposed all jury awards against tobacco companies and blamed smokers entirely for their own problems. Yet, these young guys had no knowledge of the tremendous resources devoted to making smokers: selling of Cool, denial of dangers (and/or minimizing perceptions of said dangers) all the while breeding more and more addictive tobacco. They had never heard of any of that and were not entirely sure that they believed me.

In the last few years, my husband and I (both never-smokers) have sought out a number of classic films and TV shows – mainly from the 1930s to very early 1960s. We are often struck by product placement, but especially the role of smoking, and often think that, were we teens or preteens of the period, we would certainly identify with the smokers, who were invariably smarter and so much cooler than the others.

Those vintage ads are very compelling societal examples of pervasive marketing persuasion, aren’t they? When my Dad quit smoking when I was a baby (utterly unheard of back then for any kind of ‘manly man’!), his friends and colleagues all had the same question for him: “Are you SICKLY or something?”