There’s a pervasive haze of “If you build it, they will come!” in tech circles these days. Technology, as Evgeny Morozov proposes, can be a force for improving life – but only if we keep “solutionism” in check.

There’s a pervasive haze of “If you build it, they will come!” in tech circles these days. Technology, as Evgeny Morozov proposes, can be a force for improving life – but only if we keep “solutionism” in check.

The author of To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism describes the ideology of solutionism as being essential to helping Silicon Valley maintain its image. For example:

“The technology press – along with the meme-hustlers at the TED conference – are only happy to play up any solutionist undertakings. ‘Africa? There’s an app for that!’ reads a real headline on the website of the British edition of Wired.

“Shockingly, saving the world usually involves using Silicon Valley’s own services. As Mark Zuckerberg put it in 2009, ‘The world will be better if you share more.’

“Whenever technology companies complain that our ‘broken’ world must be fixed, our initial impulse should be to ask: how do we know our world is broken in exactly the same way that Silicon Valley claims it is?

“What if the engineers are wrong?”

As I’ve written about here, my concern as a heart patient tends to focus on technology as it relates to health care specifically. But – oddly enough – I’m not particularly interested in the outliers of the Quantified Self movement, or in the so-called early adopters of technology who represent the “worried well” among us – obsessively tracking their weight, mood, sex life, diet, exercise, sleep, daily stressors and any other health indicators remotely trackable in life, simply because they can – and then distributing these fascinating graphs to all their friends online as if anybody else actually cares.

These tech-savvy folks are already on high alert to snatch up The Next Big Thing coming down the digital hypemeister pipeline, and, in my opinion as a dull-witted heart attack survivor, rarely represent in any significant fashion the Real Live Patients I know and read about and hear from daily. Actual sick people, it turns out, may well be the least likely to be able to or be interested in participating (as the obsessed worried well love to do) in digital health technology. (See also my Heart Sisters post: When The Elephant in the Room Has No Smartphone )

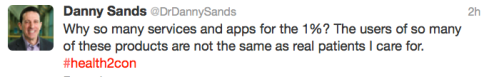

Or as Dr. Danny Sands (founder and former president of the Society for Participatory Medicine) astutely observed in this tweet during last year’s Health 2.0 conference in San Francisco:

We also know that only 5% of smartphone apps (including health care apps) are still in use within 30 days of initial download. Approximately 26% of apps are used only once, and 74% discontinued by the tenth use. A study last March by the Consumer Health Information Corporation concluded:

“Patients will not use a smartphone app simply because it is innovative. Instead, they want something that is convenient and will help them simplify their health-related tasks.”

And meanwhile, across the pond in the U.K., Oxford professor Dr. Susan Greenfield told The New York Times that up until now, most technologies have served as a means to an end:

“The printing press enabled you to read both fiction and fact that gave you insight into the real world. A fridge enabled you to keep your food fresh longer. A car or a plane enabled you to travel farther and faster.

“But current technologies have been converted from being means to being ends.

“Instead of complementing or supplementing or enriching life in three dimensions, an alternative life in just two dimensions — stimulating only hearing and vision — seems to have become an end in and of itself.

“So what concerns me is not the technology in itself, but the degree to which it has become a lifestyle rather than a means to improving your life.”

If respected cardiologist-turned-nationally-known-wireless-medicine evangelist Dr. Eric Topol has anything to say about it, he’ll continue to dine out on his whizbang stories of saving lives on airplanes thanks to his latest, greatest tech tools. The La Jolla physician’s most recent plane miracle happened when a fellow passenger on a United flight from New Orleans to Houston fell ill with nausea and an irregular heart rate. Topol was sitting a few rows ahead of the woman and responded by taking his AliveCor heart monitor out of his bag, clicking it onto his smartphone, and using it to diagnose her condition. Topol later told the San Diego Union Tribune:

“It was unequivocal that she had atrial fibrillation. It is the most common form of heart arrhythmia. It puts a person at increased risk for stroke.”

Topol “calmed and stabilized the patient” and the plane was able to land without further incident about 90 minutes later.

Tech-watchers were instantly abuzz over this story. Far less excited, however, was Florida physician Dr. Howard Green’s measured response:

“Almost every med student and doctor can relay a story of a medical incident on a plane in which they were called on to diagnose and sometimes treat acute illnesses.”

“A simple finger on the wrist also can diagnose an arrhythmia, the portable defibrillators on board do the same. Had the patient unfortunately died from the arrhythmia, I doubt the news would have been about the device that Topol was holding in his hand.”

As a testament to the speed of tech launches, by the way, AliveCor already has company in the marketplace. An over-the-counter device called ECG Check has just received clearance from the FDA.

Ironically, no sooner did Dr. Topol finish showing a couple of slides onstage during his New Orleans conference keynote address about how he uses his beloved Zeo sleep-tracking device to track his own sleep patterns that we suddenly learned that Zeo is now out of business, perhaps the inevitable victim of increasing competition from simpler tracking devices. If the same fate awaits AliveCor, maybe Dr. Topol ought to consider picking up the ECG Check for his next flight, just in case . . .

In his book To Save Everything, Click Here, Evgeny Morozov pinpoints the mantra of solutionism in the recurring description of most entrenched institutions as “broken”. Education is broken. Health care is broken. The Postal Service is broken. Wall Street is broken.

Solutionism is especially prevalent, he believes, in Silicon Valley where start-up founders are encouraged to pitch to potential investors in terms of the problems they plan to solve. He writes:

“Silicon Valley is already awash with plans for improving just about everything under the sun: politics, citizens, publishing, cooking.

“But most public institutions should not be held to the same standards as their private counterparts since their mission is to provide goods and services that markets cannot or should not provide.”

Morozov talked to The Daily Beast recently about a digital fork that was the darling of this year’s Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas. Basically, the HAPIfork vibrates when you’re eating too quickly. As if that’s not fabulous enough, it also measures:

Morozov talked to The Daily Beast recently about a digital fork that was the darling of this year’s Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas. Basically, the HAPIfork vibrates when you’re eating too quickly. As if that’s not fabulous enough, it also measures:

- how long it took to eat your meal

- the amount of “fork servings” taken per minute

- intervals between “fork servings”

This information is then uploaded via USB to your Online Dashboard to track your “progress”. But Morozov warns:

“When a Silicon Valley company tries to solve the problem of obesity by building a smart fork that will tell you that you’re eating too quickly, this is a very particular type of solution that basically puts the onus for reform on the individual.

“You treat the fact that the food industry might be manipulating the advertising, or that you might not have access to farmer’s markets in your area – all of those questions are bracketed out, and you as a consumer or citizen are basically forced to accept the current system as a given.

“We need to become a little more cautious about our celebration of innovation.

“We need to think about this before we unleash our innovations onto the world – and not afterwards. Because what happens afterwards is that we are told that, “Hey, technology is here to stay, and we just need to adapt our norms.”

“It has very little to do with the unanticipated uses. It has to do with complete disregard for issues that may not matter in Silicon Valley, where everyone is very happy.”

Morosov describes the internet, for example, as a breeding ground not of activists, but of slacktivists — people who think that clicking on a Facebook petition, for example, actually counts as a political act. He adds:

“The temptation of the digital age is to fix everything – from crime to corruption to pollution to obesity – by digitally quantifying, tracking, or gamifying behavior.”

See also:

- When the elephant in the room has no smartphone

- Self-tracking device? Got it. Tried it. Ditched it.

- Self-tracking tech revolution? Not so fast…

- When does mindfulness become mind-numbing?

- The Quantified Self meets The Urban Datasexual

.

If doctors cannot diagnose most cases of atrial fibrillation with pulse check (and a stethoscope would be nice) they are missing more than an app: they are missing basic physical diagnosis skills.

As with each medication, technology has effects and side effects (benefits and harms). Proceed with caution. Beware of salesmen…be they self-described salesmen or an unwitting sales force (health care workers).

Brings to mind an excellent book by Neil Postman called “Technopoly”.

Thanks for your perspective, Mark. But a simple pulse check wouldn’t capture media headlines, right?

I am a great fan of Morozov as well, and I think he gets at a lot of the mush around technology and its use very well.

I do think, however, if that technology is designed with the end purpose in mind, and in the case of health, from the perspective of health care practitioners and patients, it can help.

Self-tracking within reason can help patients monitor their condition, activity trackers may provide additional motivation to some to be more active, and some of the larger diagnostic equipment will likely be replaced over time by smart phone accessories and apps.

Topol is over the top in his thinking but his smart phone app, ECG in a pocket if I understand correctly, may eventually replace the larger equipment in use today.

But a general skeptical approach is likely to be more realistic.

Hello Andrew and thank you for your comments here. I suspect you’re right – somewhere between the two extremes (the headline grabbers and the Luddites!) lies a middle ground where future patients will be routinely assisted via (smaller!) technology.

Technology is not the holy grail developers and early adopters seem to think it is.

Jessie Gruman in her open letter to Mobile Health App Developers, wrote: “We—patients and caregivers need your help to reduce the demands of self care. Mobile health (mHealth) apps have enormous potential to lessen our burdens. But our needs are often only loosely related to what clinicians and/or the evidence expect us to do.”

She also quotes Amy Tenderich, founder of Diabetes Mine: “We will use tools that answer our questions and solve our problems. We will avoid tools that help us do what you think we should do and we won’t use tools that add to the work of caring for ourselves.”

Thank you so much for the tip about Jessie’s article (I’d missed it entirely!) You’re right – technology (in and of itself) is not the holy grail that developers and early adopters seem to believe it to be.

Carolyn, you are an eloquent and entertaining blogger – quite unique by my experience. This blog is particularly relevant to my work in healthcare in the UK where we are investigating how digital technology can be used as an enabler in healthcare delivery, rather than as a means to an end in itself.

I’m currently reading Cognitive Surplus by Clay Shirky and in his ruminations reflects on some research carried out on how McDonalds could improve their milkshakes. Rather than just evaluate the characteristics with customers as many researchers were doing, one looked at the people buying the shakes to determine why they bought one in the first place. The reason is meaningless, not least because it’s about McDonalds marketing strategy, but the question he ended up asking is pivotal – As a customer [patient], what job am I hiring this milkshake [product] for?

If a digital developer understood the fundamental needs of the patient, which I believe have to be described in patient-centred terms as above, then apps and digital health products and services would probably be very different in form and function.

Thanks, great reading!

@CharlieY

Thanks for your kind words, Charlie, and for your interesting (and oddly appropriate!) analogy of the McDonald’s milkshake!

Pingback: Smart Healthcare

Pingback: Smart Healthcare